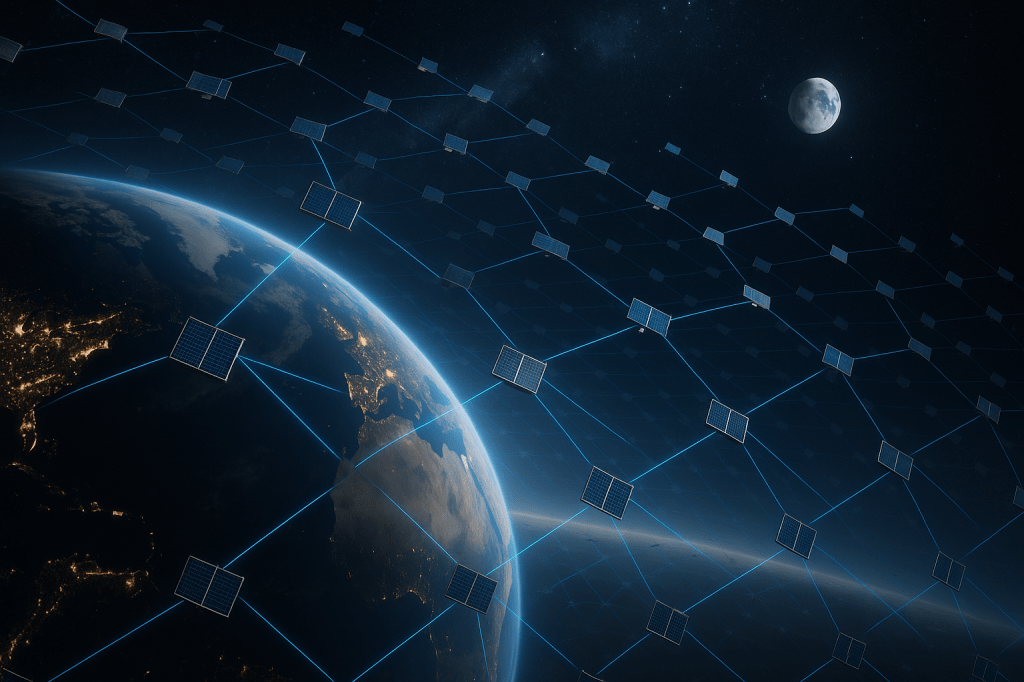

Overview: SpaceX, the FCC, and a proposal for one million satellites

SpaceX has asked the Federal Communications Commission for permission to operate a proposed constellation of up to one million solar powered data center satellites in low Earth orbit. The filing describes a fleet of small orbital platforms that would host compute resources, run on solar arrays, and communicate with each other using laser links. SpaceX framed the plan as a long term step toward distributed compute in orbit.

This request raises big questions for regulators, scientists, and everyday users. The filing touches on hardware, launch logistics, spectrum use, and space safety. Regulators are likely to scrutinize any plan at this scale, and approval for the full proposal is not likely to be immediate or unconditional.

What the FCC filing actually requests

Key points from the filing, stated simply:

- Scale: authorization to operate up to one million satellites in low Earth orbit, sometimes abbreviated LEO.

- Power: satellites would be solar powered, drawing energy from onboard solar arrays.

- Communications: use of inter satellite laser links, so satellites could pass data by light instead of radio waves.

- Mission: provide compute services in orbit, described as a step toward massively distributed orbital computing, rather than only delivering internet connectivity.

Why this matters to ordinary readers

Most people will not run code in orbit, but the proposal could affect everyday services and scientific observation. If regulators approve large constellations, we could see changes in how cloud and edge computing is delivered, how satellite traffic is managed, and how night skies are seen from Earth.

Decisions made by the FCC and similar agencies will influence costs, launch schedules, and rules to protect astronomy and orbital safety. These decisions will have downstream effects on internet latency, service reliability, and environmental concerns.

Quick summary for non experts

- SpaceX wants a massive network of small satellites that provide computing power in orbit.

- The satellites would run on solar power and link to each other with lasers.

- The idea raises technical, regulatory, and environmental questions that affect science and public policy.

Technical feasibility

Putting compute hardware into LEO is possible, but it has hard engineering limits. Several technical areas need careful consideration.

Power generation

Solar panels can generate electricity in orbit, but available power is limited by size, orientation, and eclipse periods when a satellite is in the Earths shadow. Data center servers consume significant energy; making compact satellites that carry both useful compute and enough solar capacity is a major design challenge.

Thermal management

Space is cold, but thermal control is difficult. Without air, satellites cannot use fans and typical air cooling used in ground data centers. Heat must be radiated into space, which requires heavy and sometimes bulky radiators. Managing heat for many servers inside a small package will be a major constraint.

Compute hardware and maintenance

Servers in space will face radiation, atomic oxygen, and component degradation. Repair or upgrades are far harder than in terrestrial data centers. Redundancy and fault tolerant design will be essential, but redundancy raises mass and cost.

Laser communications

Lasers can move large amounts of data between satellites with lower latency and less spectrum use than radio. However laser links require precise pointing, line of sight, and tight alignment. Atmospheric weather does not affect space to space links, but ground to space laser links can be complicated. Scaling lasers to one million nodes is an engineering and testing problem.

Launch and deployment logistics

Getting one million satellites into orbit would be unprecedented. Practical questions include launch cadence, cost per launch, manufacturing throughput, and integration logistics.

- Launch cadence, meaning how often rockets fly, would need to increase dramatically to deploy or replace many satellites.

- Cost estimates hinge on reuse, rideshare opportunities, and manufacturing scale. SpaceX has lowered launch costs with reusable rockets, but the manufacturing and assembly of a million nodes is a separate challenge.

- Rideshare versus dedicated launches would shape deployment. Rideshares carry small satellites on larger missions, but coordinating many rideshares adds operational complexity.

Regulatory and licensing hurdles

The FCC regulates many aspects of commercial satellite operations in the United States, including spectrum use and licensing. A request for up to one million satellites triggers broader reviews.

- The FCC will evaluate spectrum allocation, potential interference with other services, and coordination with international regulators.

- Other agencies may also weigh in; for example agencies that focus on national security, export controls, and environmental review could raise additional requirements.

- Full authorization for a large network is unlikely to come without staged approvals, technical demonstrations, and interagency coordination.

Space sustainability and debris risk

Adding large numbers of satellites increases the risk of collisions and long term debris. Collisions create fragments that can endanger other satellites and create cascading risks.

Key concerns:

- Collision probability increases as orbital traffic rises, even if individual satellites are small.

- End of life disposal must be reliable, with plans for deorbiting or moving to graveyard orbits.

- Operators will need robust tracking, collision avoidance maneuvers, and international coordination to reduce risk.

Astronomical and environmental impacts

Large satellite constellations have already affected ground based astronomy. Bright reflections and radio interference can reduce the quality of astronomical observations.

Solar powered satellites can still reflect sunlight, and a million small platforms could increase light pollution. Radio quiet observing could be affected if ground links use frequencies near scientific bands.

Market and strategic motivations

Why consider orbital compute at all? There are possible advantages and target use cases.

- Latency sensitive applications, such as some financial systems, real time analytics, and remote sensing, could benefit from compute closer to where data is generated.

- Global coverage for regions with limited terrestrial infrastructure could be an advantage, especially for remote sensing and data processing near collection points.

- Strategic reasons may include offering differentiated services beyond traditional ground based cloud providers, and testing new business models for edge computing.

Economic realism

Comparing orbital data centers with terrestrial ones shows trade offs.

- Terrestrial data centers benefit from cheap power, mature cooling systems, and easier maintenance and upgrades.

- Orbit offers low latency to certain endpoints and global reach, but at higher launch costs, more complex operations, and limited power and cooling.

- For many mainstream cloud tasks, ground based infrastructure will remain more cost effective for the foreseeable future.

Precedent and competitive landscape

SpaceX is not the only company exploring space based infrastructure. Previous and ongoing projects include satellite internet constellations and experimental small satellites that carry specialized payloads. Companies and national agencies are testing edge compute on high altitude platforms and space stations.

These efforts offer technical lessons, but none to date have proposed the mass scale described in the SpaceX filing.

Ethical and geopolitical implications

Orbital compute raises questions about control, jurisdiction, and privacy. If data processing moves off planet, questions appear about which laws apply and how oversight will work.

Considerations include:

- Who has regulatory authority over data processed in orbit?

- How will governments ensure compliance with domestic privacy and surveillance laws?

- Could space based computing shift strategic advantage to entities that control orbital networks?

Key takeaways

- SpaceX has filed with the FCC to operate up to one million solar powered satellites that could host compute workloads in low Earth orbit, using laser links for data transfer.

- The idea is technically possible in parts, but power, thermal management, reliability, and maintenance are major challenges.

- Deployment at this scale would require unprecedented launch and manufacturing capacity, and is likely to face staged regulatory review.

- Large constellations increase collision and debris risk, and could affect ground based astronomy through reflections and potential radio interference.

- For many current cloud tasks, terrestrial data centers will remain more cost effective, but orbital compute could find niche use cases that value global reach or extreme latency reduction.

FAQ

Q Will these satellites act like floating Amazon or Google data centers?

A Not exactly. The proposal aims to deliver compute in orbit, but constraints on power, cooling, and maintenance mean these satellites would be smaller and less capable than large ground based data centers. They could support particular use cases rather than replace terrestrial clouds.

Q Could this make internet services faster for everyone?

A Some applications that need low latency or global coverage might benefit. For typical consumer web traffic, improvements are unlikely to be dramatic compared with existing ground based networks.

Q What about the risk to astronomy?

A Large numbers of satellites increase the chance of visible reflections and radio interference. Astronomers have already raised concerns about earlier constellations. Any new program will be examined for its potential impact on scientific observation.

Conclusion

SpaceX has proposed an ambitious move into orbital computing, asking the FCC for authorization to operate as many as one million solar powered satellites that communicate with lasers. The filing highlights potential future capabilities, but several hard questions remain. Engineers must solve power and thermal limits, operators must manage launches and debris risk, and regulators must balance innovation with safety and scientific integrity.

Approval for a constellation at this scale will not be simple or fast. Expect a careful, staged review process, technical demonstrations, and debates over environmental and legal implications. For most users, the change will be gradual, and terrestrial data centers will continue to provide the bulk of cloud services for the near term.

Leave a comment